17 ÃÆà ½Ãâò-estradiol induced oxidative stress in gill, brain, liver, kidney and blood of common carp (Cyprinus carpio)

Adriana Andrea Gutiérrez-Gómez, Nely San Juan-Reyes, Marcela Galar-Martínez, Octavio Dublán-García, Hariz Islas-Flores, Sandra García-Medina, Itzayana Pérez-Alvárez, Leobardo Manuel Gómez-Oliván

1 Environmental Toxicology Laboratory, Department of Chemistry, University of the State of Mexico. Paseo Colon Paseo Tollocan intersection s / n. Col. Residencial Colon, 50120 Toluca, State of Mexico, Mexico;

2 Aquatic Toxicology Laboratory, Department of Pharmacy, National School of Biological Sciences, National Polytechnical Institute. Plan de Ayala y Carpio s/n, 11340 Mexico DF, Mexico. Professional Unit Adolfo Lopez Mateos Av. Wilfrido Massieu Esq. Cda. Miguel Stampa s/n, Gustavo A. Madero. Mexico DF. Mexico. C.P.07738.

- Corresponding Author:

- Leobardo Manuel Gómez-Oliván

Environmental Toxicology Laboratory

Department of Chemistry

University of the State of Mexico. Paseo Colon Paseo Tollocan intersection s / n. Col. Residencial Colon

50120 Toluca, State of Mexico, Mexico

Tel: 527222173890

Fax: 527222173890

E-mail: lmgomezo@uaemex.mx; lgolivan74@gmail.com

Received date: January 27, 2016; Accepted date: February 01, 2016; Published date: February 07, 2016

Citation: Gómez-Oliván LM, Gutiérrez-Gómez AA, Juan-Reyes NS, et al., 17 ß-Estradiol Induced Oxidative Stress in Gill, Brain, Liver, Kidney and Blood of Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). Electronic J Biol, 12:1

Abstract

Title 17 β-estradiol-induced oxidative stress in gill, brain, liver, kidney and blood of common carp (Cyprinus carpio)

Background Endocrine-disrupting chemicals are of great public and scientific concern, since these chemicals can mimic, block, or interfere with hormones in the body and can subsequently induce detrimental effects on reproductive processes in wildlife and in humans. Estrogenic compounds such as 17 β-estradiol can reach the aquatic environment because wastewater treatment plants are not sufficiently effective in reducing and/or removing these contaminants, damaging the organisms living there. This study aimed to evaluate the oxidative stress induced by 17 β-estradiol in gill, brain, liver, kidney and blood of C. carpio.

Methods and Findings Carp were exposed at environmentally relevant concentrations (1 ng L-1, 1 ?g L-1 and 1 mg L-1) for different exposure periods (12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h), and the following biomarkers were evaluated: hydroperoxide content (HPC), lipid peroxidation (LPX), protein carbonyl content (PCC), and the activity of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx). Statistically significant increases with respect to the control group (P<0.05) were observed in HPC, LPX and PCC at all concentrations particularly in kidney and blood of exposed specimens. SOD, CAT and GPx activity also increased at all concentrations in the same organs with respect to the control group.

Conclusion The estrogenic compound 17 β-estradiol induce oxidative stress in common carp (Cyprinus carpio).

Keywords

17 -estradiol; Cyprinus carpio; Oxidative stress; Biomarkers.

1. Introduction

A variety of chemical contaminants, such as pesticides, hydrocarbons, personal care products, solvents, detergents and pharmaceutical agents, enter the aquatic environment through the discharge of wastewater of pharmaceutical industry, hospitals and homes. Pharmaceuticals once administered can be excreted as the parent compound or active metabolites, and can reach the environment to variable extents (Zuccato). Has been shown current wastewater treatment systems are not sufficiently effective in reducing and/or removing these contaminants [1]. Once in the environment, these compounds are considered “emerging contaminants”. Richards define these as unregulated compounds that can pose a risk to aquatic ecosystems [2].

Such emerging contaminants include estrogens, a heterogeneous group of environmental contaminants able to influence and modify endocrine functions in animals, and are thus termed endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) [3]. EDCs have been defined by the Organization of Economic and Cooperative Development (OECD) as “an exogenous substance or mixture that alters the function(s) of the endocrine systems and consequently causes adverse health effects in an intact organism, or its progeny or (sub) populations” [4]. In this broad class of chemicals are included the synthetic steroids (17-α-ethinylestradiol (EE2), mestranol) are used as contraceptives [5], the natural estrogens, such as estrone (E1), 17β-estradiol (E2), and estriol (E3) (Zhu et al.), are predominantly female hormones, responsible for the maintenance of the health of reproductive tissues, breast, skin and brain [6].

Cytochrome P450 plays a critical role in the oxidative metabolism of endogenous compounds such as steroids and other xenobiotics [7]. Estrogens undergo hydroxylation, reduction, methylation or oxidation reactions followed by conjugation in the liver, in order to be excreted [8]. E2 is the major estrogen secreted by the ovaries and further oxidized into estriol for elimination. E2 is naturally excreted in female as 2.3-259 μg/person/day and in male as 1.6 μg/person/ day [9].

The hormones can end up in the environment through sewage discharge or animal waste disposal [10]. EDCs are found in aquatic environments at concentrations ranging from ng L-1 to μg L-1 [11,12]. In the raw sewage of the Brazilian STPs was detected E2 at 21 ng L-1 [13]. Average concentrations of E2 in influents of six Italian activated sludge STPs was 12 ng L-1 [14]. The concentrations of this hormone in influents of Japanese STPs ranged from 30 to 90 ng L-1 in autumn and from 20 to 94 ng L-1 in summer [15]. The concentration detected of E2 in surface waters of South Florida coastal was 1.8 ng L-1 [16]. In lake Van of Turkey, the concentrations in water and sediment were 0.996 ng L-1 and 0.098 ng g-1, respectively [17]. In sewage effluents of “Río de la Plata”, Argentina, concentrations detected of E2 were between 122 and 631 ng L-1, and in surface waters at 369 ng L-1 [18]. In Mexico, studies on the occurrence of this type of compounds have been carried out in Xochimilco wetland, concentrations from 0.11 ng μL-1 to 1.72 ng μL-1 have been detected [19].

Although pharmaceuticals are designed to target humans, the steroid hormones are of special concern due to their potency because aquatic organisms with the right receptors could also experience pharmacodynamic effects. Secondary effects not considered important in the treatment of humans may have major implications for non-mammalian aquatic organisms [20]. These compounds can induce biological effects at very low concentrations of 0.1 ng L-1 [21].

Diverse studies have reported E2-induced toxicity in aquatic organisms, since these organisms are more susceptible to toxic effects due to their continued exposure to wastewater discharges throughout the life cycle [22]. E2 induce oxidative stress in Dicentrarchus labrax L. and Lateolabrax japonicus [23,24], also generates induction of vitellogenin and vitelline envelope proteins [25,26], altered/abnormal blood hormone levels, reduced fertility and fecundity, masculinization of females and feminisation of males [27-30].

A variety of biomarkers have been used to monitor the effect of E2 on fish such as genotoxicity, lipid peroxidative damage and antioxidant responses [23,31]. A biomarker is a cellular, molecular, genetic or physiologic response altered in an organism or population in response to a chemical stressor [32]. Xenobiotics present in the environment can stimulate the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which results in oxidative damage to aquatic organisms [33]. ROS include the superoxide anion radical (O2 .), its conjugated acid, hydroperoxide (HO2), hydroxyl radicals (OH.) and the radical species hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [34]. Oxidative stress (OS) results from the metabolic reactions that use oxygen and represents an imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant systems in living organisms [35]. ROS production can be decreased or reversed by several enzymes, called antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) [36]. Nevertheless, at high concentrations, ROS can be important mediators of damage to cell structures, nucleic acids, lipids and proteins [37].

Bioindicators can be used to evaluate the toxic impact of contaminants in water bodies. Fish have been recognized as major vectors for contaminant transfer to humans [38]. The common carp Cyprinus carpio is frequently used as a bioindicator species [39] in toxicological assays due to its commercial importance and wide geographic distribution as well as its easy maintenance and handling in the laboratory [40,41]. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the oxidative stress induced by 17 β-Estradiol in gill, brain, liver, kidney and blood of C. carpio.

2. Methods

2.1 Specimen collection and maintenance

Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) 18.39 ± 0.31 cm in length and weighing 50.71 ± 7.8 g were obtained from the aquaculture facility in Tiacaque, State of Mexico. Fish were safely transported to the laboratory in wellsealed polyethylene bags containing oxygenated water, then stocked in a large tank with dechlorinated tap water (previously reconstituted with salts) and acclimated to test conditions for 30 days prior to beginning of the experiment. During acclimation, carp were fed Pedregal Silver™ fish food, and threefourths of the tank water was replaced every 24 h to maintain a healthy environment. The physicochemical characteristics of tap water reconstituted with salts were maintained, i.e. temperature 20 ± 2°C, oxygen concentration 80-90%, pH 7.5-8.0, total alkalinity 17.8 ± 7.3 mg L-1, total hardness 18.7 ± 0.6 mg L-1. A natural light/dark photoperiod was maintained.

Oxidative stress determination

Test systems consisting in 120 × 80 × 40 cm glass tanks filled with water reconstituted from the following salts: NaHCO3 (174 mg L-1, Sigma-Aldrich), MgSO4 (120 mg L-1, Sigma-Aldrich), KCl (8 mg L-1, Vetec) and CaSO4.2H2O (120 mg L-1, Sigma-Aldrich) were maintained at room temperature with constant aeration and a natural light/dark photoperiod. Static systems were used and no food was provided to specimens during the exposure period. Three environmentally relevant concentrations were tested (1 ng L-1, 1 μg L-1, and 1 mg L-1). Kinetics was run for the following exposure periods: 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. A 17 β-estradiol-free control system with six carp was set up for each exposure period, and sublethal assays were performed in triplicate. A total of 180 fish were used in these assays. At the end of the exposure period, fish were removed from the systems and placed in a tank containing 50 mg L-1 of clove oil as an anaesthetic [42]. Anesthetized specimens were placed in a lateral position. Blood was removed with a heparinized 1 mL hypodermic syringe by puncture of the caudal vessel performed laterally near the base of the caudal peduncle, at midheight of the anal fin and ventral to the lateral line.

After puncture, specimens were placed in an ice bath and sacrificed. The gill, brain, liver and kidney were removed, placed in phosphate buffer solution pH 7.4 and homogenized. The supernatant was centrifuged at 12,500 rpm and –4ºC for 15 min. The following biomarkers were then evaluated: HPC, LPX, PCC and the activity of the antioxidant enzymes SOD, CAT and GPX. All bioassays were performed on the supernatant.

Determination of HPC: HPC was determined by the Jiang et al. method [43]. To 100 μL of supernatant (previously deproteinized with 10% trichloroacetic acid) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added 900 μL of the reaction mixture [0.25 mM FeSO4 (Sigma-Aldrich), 25 mM H2SO4 (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1 mM xylenol orange (Sigma-Aldrich) and 4 mM butyl hydroxytoluene (Sigma-Aldrich) in 90% (v/v) methanol (Sigma- Aldrich)]. The mixture was incubated for 60 min at room temperature, and absorbance was read at 560 nm against a blank containing only reaction mixture. Results were interpolated on a type curve and expressed as nanomolars cumene hydroperoxide (CHP; Sigma-Aldrich) per milligram of protein.

Determination of LPX: LPX was determined by the Büege and Aust method [44]. To 100 mL of supernatant was added Tris-HCl buffer solution pH 7.4 (Sigma- Aldrich) to attain a volume of 1 mL. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min; 2 mL thiobarbituric acid (TBA)-trichloroacetic acid (TCA) reagent [0.375% TBA (Sigma-Aldrich) in 15% (TCA, Sigma-Aldrich)] was added, and samples were shaken in a vortex. They were then heated to boiling for 45 min, allowed to cool, and the precipitate removed by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Absorbance was read at 535 nm against a reaction blank. Malondialdehyde (MDA) content was calculated using the molar extinction coefficient (MEC) of MDA (1.56 × 105 M cm-1). Results were expressed as nanomolars of MDA per milligram of protein.

Determination of PCC: PCC was determined using the method of Levine et al. [45] as modified by Parvez and Raisuddin [46]. To 100 μL of supernatant was added 150 μL of 10 mM DNPH (Sigma-Aldrich) in 2 M HCl (Sigma-Aldrich), and the resulting solution was incubated at room temperature for 1 h in the dark. Next, 500 μL of 20% trichloroacetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was added, and the solution was allowed to rest for 15 min at 4°C. The precipitate was centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 5 min. The bud was washed several times with 1:1 ethanol:ethyl acetate (Sigma-Aldrich), then dissolved in 1 mL of 6 M guanidine (Sigma-Aldrich) solution (pH 2.3) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Absorbance was read at 366 nm. Results were expressed as micromolar reactive carbonyls formed (C=O) per milligram of protein, using the MEC of 21,000 M cm-1.

Determination of SOD activity: SOD activity was determined by the Misra and Fridovich method [47]. To 40 μL of supernatant in a 1 cm cuvette was added 260 μL carbonate buffer solution [50 mM sodium carbonate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1 mM EDTA (Vetec)] pH 10.2, plus 200 μL adrenaline (30 mM, Bayer). Absorbance was read at 480 nm after 30 s and 5 min. Enzyme activity was determined using the MEC of SOD (21 M cm-1). Results were expressed as millimolars SOD per milligram of protein.

Determination of CAT activity: CAT activity was determined by the Radi et al. method [48]. To 20 mL of supernatant was added 1 mL isolation buffer solution [0.3 M saccharose (Vetec), 1 mL EDTA (Vetec), 5 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich) and 5 mM KH2PO4 (Vetec)], plus 0.2 mL of a hydrogen peroxide solution (20 mM, Vetec). Absorbance was read at 240 nm after 0 and 60 s. Results were derived by substituting the absorbance value obtained for each of these times in the formula: CAT concentration= (A0-A60) /MEC), where the MEC of H2O2 is 0.043 mM cm-1, and were expressed as micromolars H2O2 per milligram of protein.

Determination of GPx activity: GPx activity was determined by the Gunzler and Flohe-Clairborne [49] method as modified by Stephensen et al. [50]. To 100 μL of supernatant was added 10 μL glutathione reductase (2 U glutathione reductase, Sigma-Aldrich) plus 290 μL reaction buffer [50 mM K2HPO4 (Vetec), 50 mM KH2PO4 (Vetec) pH 7.0, 3.5 mM reduced glutathione (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM sodium azide (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.12 mM NADPH (Sigma-Aldrich)] and 100 μL H2O2 (0.8 mM, Vetec). Absorbance was read at 340 nm at 0 and 60 s. Enzyme activity was estimated using the equation: GPx concentration= (A0-A60) /MEC), where the MEC of NADPH=6.2 mM cm-1. Results were expressed as millimolars NADPH per milligram of protein.

Determination of total protein: Total protein was determined by the Bradford method [51]. To 25 μL of supernatant were added 75 μL deionized water and 2.5 mL Bradford’s reagent [0.05 g Coommassie Blue dye (Sigma-Aldrich), 25 mL of 96 % ethanol (Sigma- Aldrich), and 50 mL H3PO4 (Sigma-Aldrich), in 500 mL deionized water]. The test tubes were shaken and allowed to rest for 5 min prior to the reading of absorbance at 595 nm and interpolation on a bovine albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) curve.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Results of sublethal toxicity assays were statistically evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and differences between means were compared using the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test, with P set at <0.05. Statistical determinations were performed with SPSS v10 software (SPSS, Chicago IL, USA).

3. Result

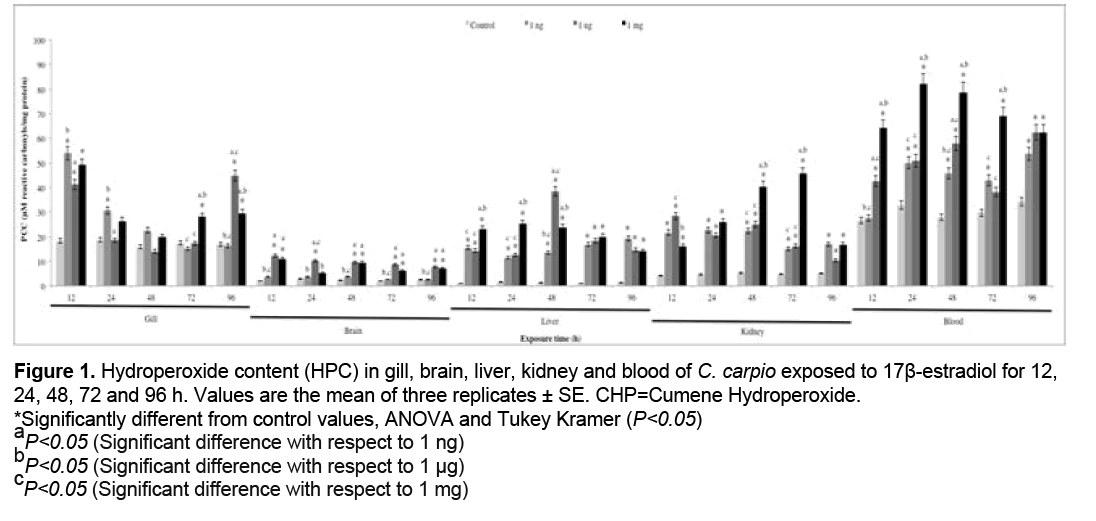

3.1 HPC

HPC results are shown in Figure 1. A significant increase with respect to the control group (P<0.05) was observed at 1 ng in brain (12, 24, 48 and 72 h), liver (24, 48, 72 and 96 h), kidney (24 and 48 h) and blood (12, 48, 72 and 96 h), at 1 μg in gill, brain, liver, kidney (all exposure times) and blood (12, 24 h), and at 1 mg in gill, brain, liver (all exposure times), kidney (24, 48 and 72 h) and blood (24 and 96 h).

Figure 1: Hydroperoxide content (HPC) in gill, brain, liver, kidney and blood of C. carpio exposed to 17β-estradiol for 12,

24, 48, 72 and 96 h. Values are the mean of three replicates ± SE. CHP=Cumene Hydroperoxide.

*Significantly different from control values, ANOVA and Tukey Kramer (P<0.05)

aP<0.050.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 ng)

bP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 μg)

cP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 mg)

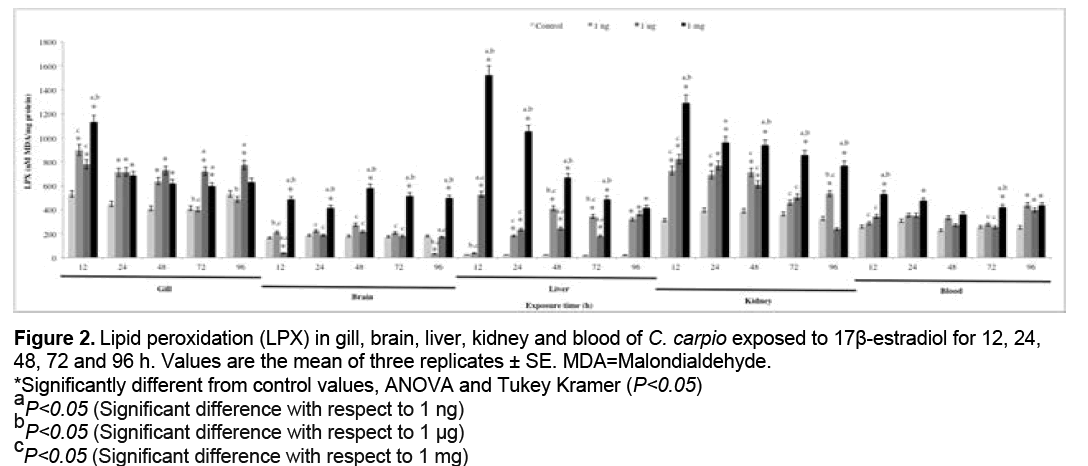

3.2 LPX

Figure 2 shows the results obtained for LPX. Significant increases with respect to the control group (P<0.05) were observed at 1 ng in gill (12, 24 and 48 h), brain and blood (96 h), liver (24, 48, 72 and 96 h), kidney (12, 24, 48, 96), at 1 μg in gill, liver (all exposure times), brain (12 h), kidney (12, 24 and 48 h) and blood (96 h), at 1 mg in gill (12, 24, 48, 72 h), brain, liver and kidney (all exposure times), blood (12, 24, 72 and 96 h).

Figure 2: Lipid peroxidation (LPX) in gill, brain, liver, kidney and blood of C. carpio exposed to 17β-estradiol for 12, 24,

48, 72 and 96 h. Values are the mean of three replicates ± SE. MDA=Malondialdehyde.

*Significantly different from control values, ANOVA and Tukey Kramer (P<0.05)

aP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 ng)

bP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 μg)

cP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 mg)

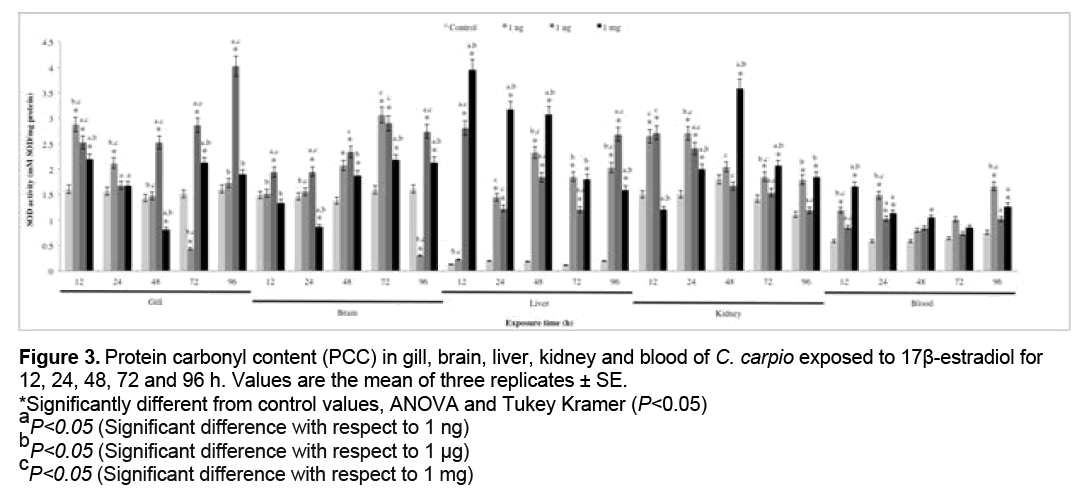

3.3 PCC

PCC results are shown in Figure 3. A significant increase with respect to the control group (P<0.05) was observed at 1 ng in gill (12 and 24 h), liver and kidney (all exposure times), blood (24, 48, 72 and 96 h), at 1 μg in gill (12 and 96 h), brain, liver, kidney (all exposure times) and blood (12, 24, 48 and 96 h), at 1 mg in gill (12, 72 and 96 h), brain (12, 48, 72 and 96 h), liver, kidney and blood (all exposure times).

Figure 3: Protein carbonyl content (PCC) in gill, brain, liver, kidney and blood of C. carpio exposed to 17β-estradiol for

12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. Values are the mean of three replicates ± SE.

*Significantly different from control values, ANOVA and Tukey Kramer (P<0.05)

aP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 ng)

bP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 μg)

cP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 mg)

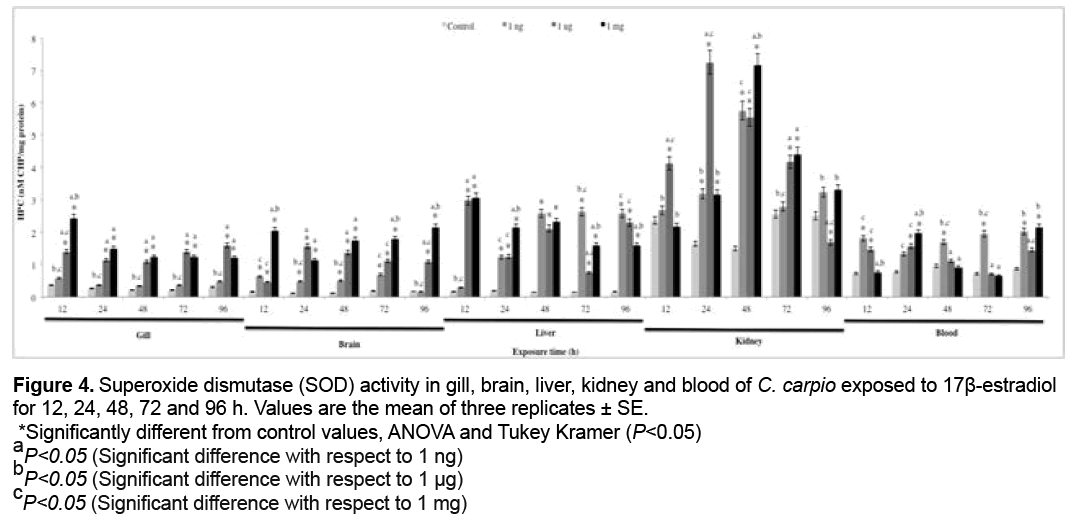

3.4 SOD activity

SOD activity results are shown in Figure 4. Significant increases with respect to the control group (P<0.05) were found at 1 ng in gill (12, 24 and 72 h), brain (48, 72 and 96 h), liver (24, 48, 72 and 96 h), kidney (12, 24, 72 and 96 h) and blood (12, 24 and 96 h), at 1 μg in gill (12, 48, 72 and 96 h), brain and liver (all exposure times), kidney (12 and 24 h) and blood (24 h), at 1 mg in gill (12, 48 and 72 h), brain (24, 48, 72 and 96 h), liver (all exposure times), kidney (24, 48, 72 and 96 h) and blood (12, 24, 48 and 96 h).

Figure 4: Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in gill, brain, liver, kidney and blood of C. carpio exposed to 17β-estradiol

for 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. Values are the mean of three replicates ± SE.

*Significantly different from control values, ANOVA and Tukey Kramer (P<0.05)

aP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 ng)

bP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 μg)

cP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 mg)

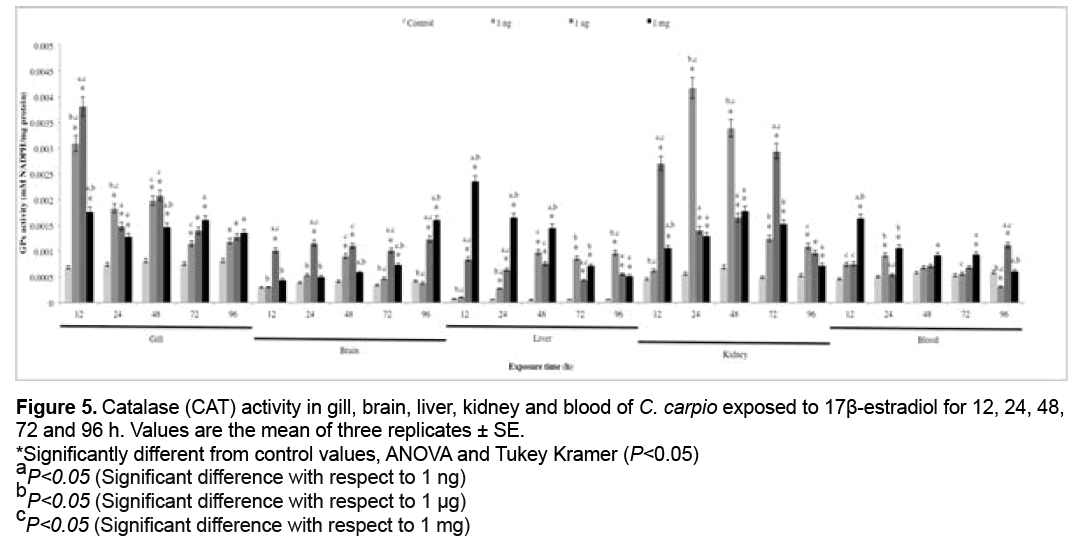

3.5 CAT activity

CAT activity is shown in Figure 5. Significant Medicines Agency [53], the approval procedure of new human pharmaceuticals requires an environmental risk assessment based on standard toxicity tests (to algae, Daphnia magna and fish) if the environmental concentration of the active ingredient is >10 ng L-1.

Figure 5: Catalase (CAT) activity in gill, brain, liver, kidney and blood of C. carpio exposed to 17β-estradiol for 12, 24, 48,

72 and 96 h. Values are the mean of three replicates ± SE.

*Significantly different from control values, ANOVA and Tukey Kramer (P<0.05)

aP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 ng)

bP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 μg)

cP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 mg)

Estrogens are chemical pollutants that can disrupt increases with respect to the control group (P<0.05) occurred at 1 ng in gill (12 and 24 h), brain and blood (all exposure times), liver (24, 48, 72 and 96 h), kidney (12, 24, 48, 72 h), at 1 μg in gill (12 and 24 h), brain, liver and kidney (all exposure times), blood (12, 24, 48 and 96 h), at 1 mg in gill (12, 24 and 48 h), brain (12, 48, 72 and 96 h) and liver, kidney and blood (all exposure times).

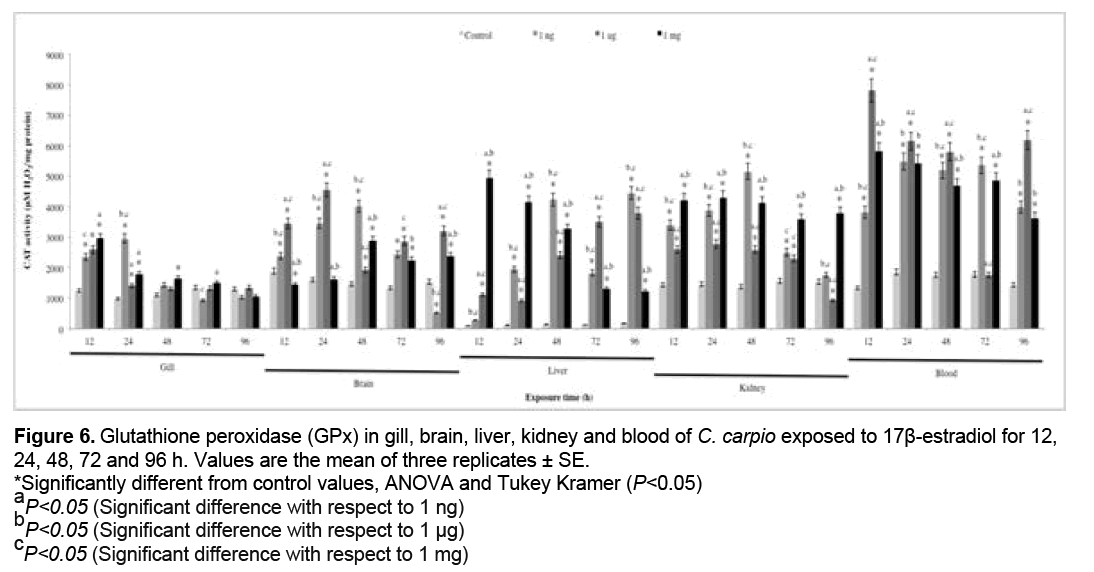

3.6 GPx activity

Gpx activity results are shown in Figure 6. Significant increases with respect to the control group (P<0.05) were recorded at 1 ng in gill (all exposure times), brain (48 h), liver and kidney (24, 48, 72 and 96 h), blood (24 and 96 h), at 1 g in gill, brain, liver and kidney (all exposure times), blood (96 h), at 1 mg in gill, liver and kidney (all exposure times), brain (72 and 96 h) and blood (12, 24, 48, 72 h).

Figure 6: Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) in gill, brain, liver, kidney and blood of C. carpio exposed to 17β-estradiol for 12,

24, 48, 72 and 96 h. Values are the mean of three replicates ± SE.

*Significantly different from control values, ANOVA and Tukey Kramer (P<0.05)

aP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 ng)

bP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 μg)

cP<0.05 (Significant difference with respect to 1 mg)

4. Discussion

Hormones are present at varying levels in effluents from sewage treatment works in countries around the world [52]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does require ecological testing and evaluation of pharmaceuticals when environmental concentration exceeds 1 μg L-1. Also, according to the current European Regulatory Guidance set by the European the endocrine system of animals by binding to and activating the estrogen receptor(s) [28]. E2 is excreted through the urine in an inactive conjugated form [54,55], but can be reconverted to an activate form possibly by the action of certain bacteria present in sewage [56]. Mammalian CYP enzymes are critical for E2 metabolism, including those belonging to the CYP1A, CYP1B, and CYP3A subfamilies. The liver is the major site of E2 metabolism; all CYP1s and CYP3As are known to be expressed in the liver of mammals [57] and fish [58,59]. Metabolism of E2 leads to the production of semiquinones and quinones, which produce free radicals through redox cycling, and a subsequent cellular damage [60].

Molecular biomarkers are used to test for oxidative damage induced in macromolecules by ROS and RNS [61]. ROS are constantly generated under normal conditions as a consequence of aerobic respiration [62]. These species are essentials for a number of biochemical reactions involved in the synthesis of prostaglandins, hydroxylation of proline and lysine, oxidation of xanthine and other oxidative processes [63]. ROS are capable of oxidizing cell constituents such as DNA, proteins, and lipids, thereby incurring oxidative damage to cell structures [64]. In the LPX, polyunsaturated fatty acids of the cell membrane react with ROS, particularly with the OH. and the reactive nitrogen species peroxynitrite (ONOO-), through a chain reaction mechanism. Hydroperoxides are formed as the primary products in lipid peroxidation and are then degraded to low molecular weight products, including MDA [65,66]. An increase in HPC (Figure 1) was observed in all organs at all concentrations tested, the kidney displaying the highest value for this biomarker. Furthermore, the level of damage to lipids is shown in Figure 2, where increased LPX is evident in all organs at the 3 concentrations and is highest in kidney. This may be explained by the fact that in the biotransformation of E2 are formed ROS such as OH., studies have suggested that teleost fish kidney contains rather high cytochrome P-450-dependent activities compared with those of the liver [67]. Fishes are rich in unsaturated membrane lipids, the most susceptible lipids to oxidative damage, and directly exposed to estrogenic compounds such E2 [32].

Results obtained in the present study are consistent with those reported in previous studies. Maria et al. report that intraperitoneal injection of E2 increases the LPX in juvenile sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) [8], while Thilagam et al. Report increased LPX in Japanese sea bass (Lateolabrax japonicus) with exposure to E2 [24]. The main metabolites of E2 include 2-, 4-, and 16α-hydroxyestradiol [68-70]. The 2- and 4-hydroxylated catechols contain the hydroxyl groups in a vicinal position, which predisposes them to further oxidation. Both can be oxidized to semiquinones, which in the presence of molecular oxygen are oxidized to quinones with formation of O2 . [71]. The latter radical reacts rapidly with the nitric oxide (NO) derived from arginine metabolism, forming ONOO− [72] which has a high binding affinity for lipids and proteins. Proteins are major targets of oxidative modifications in cells. The side chains of all amino acid residues of proteins, in particular cysteine and methionine residues of proteins are susceptible to oxidation by the action of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [73]. Carbonyls can be formed as a consequence of secondary reactions of some amino acid side chains with lipid oxidation products, such as 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) [74]. The concentration of carbonyl groups is a good measure of ROS-mediated protein oxidation [35]. As can be seen in Figure 3, PCC increased in all organs evaluated at all concentrations tested, the blood displaying the highest value for this biomarker. This may be due to the presence of O2 ., OH. and ONOO−. In particular, ONOO− is highly reactive and has a great capacity for binding to proteins and oxidizing them. Blood is susceptible of oxidative damage since, in addition to fulfilling diverse functions such as the transport of xenobiotics throughout the body, it also transports proteins and other biomolecules to all body tissues. In freshwater fish, the gills are known as a place where the enzymatic activity is enhanced, which promotes oxidative metabolism and favors the production of ROS [75]. The brain is also a target of oxidative damage since it contains a large number of proteins that are essential for brain functions and uses high quantities of O2 with the possibility of production of ROS, which bind to proteins and oxidize them [76,77].

ROS and RNS can remove protons from methylene groups in amino acids, leading to formation of carbonyls that tend to ligate protein amines and also induce damage to nucleophilic centers, sulfhydryl group oxidation, disulfide reduction, peptide fragmentation, modification of prosthetic groups and protein nitration [78]. These modifications lead to loss of protein function [79,80] and therefore also of body integrity [46].

Antioxidants are substances that either directly or indirectly protect cells against adverse effects of xenobiotics. Antioxidant levels initially increase in order to offset OS, but prolonged exposure leads to their depletion [81]. The activities of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT and GPx are important biomarkers for investigating the cellular redox milieu [32]. SOD is the first mechanism of antioxidant defense and the main enzyme responsible for the conversion of superoxide anion (O2 .) to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [82], which is metabolized to O2 and water by CAT and GPx [83]. The increases in SOD activity in all organs (Figure 4) were induced by release of the anion radical O2 . [84]. In contrast, SOD activity decreased in gill, brain with respect to the control group. This may be due to the fact that when high concentrations of reactive species are present, antioxidant enzymes are inactivated, inducing major damage on cell components [85]. Figures 5 and 6 show CAT and GPx activity, respectively. CAT and GPx activities increase in all organs, however the increase was higher in CAT. These increases can be attributed to the antioxidant capacity of organisms to offset H2O2-induced oxidative damage.The SOD, CAT and GPx increases, represent an efficient modulation of the cellular defense mechanism against oxidative stress and cellular damage in the fishes exposed to E2 [32].

Carrera et al. showed CAT activity inhibition in Sparus auratus after E2 treatment [7], whereas Solé et al. reported GPX and CAT activity decrease in E2 injected carp [86]. Maria et al. observed E2 pro-oxidant potential in D. labrax gills and liver [8]. Finally, Costa el al. conclude that CAT and SOD increases, represent an efficient modulation of the cellular defense mechanism against OS and cellular damage in the fishes exposed to E2 [32].

In conclusión, 17 β-estradiol induced oxidative stress in gill, brain, liver, kidney and blood of common carp. The set of assays used in the present study constitutes a reliable early warning biomarker for use in evaluating the toxicity induced by emerging contaminants in Cyprinus carpio.

Acknowledgement

This study was made possible by support from the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México (UAEM 3722/2014/CID).

References

- Kümmerer K. (2001). Drugs in the environment: emission of drugs, diagnostic aids and disinfectants into wastewater by hospitals in relation to other sources?a review. Chemosphere. 45: 957-969.

- Richardson SD, Plewa MJ, Wagner ED, et al. (2007). Occurrence, genotoxicity, and carcinogenicity of regulated and emerging disinfection by-products in drinking water: a review and roadmap for research. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research. 636: 178-242.

- Matozzo V, Marin MG. (2008). Can 17-ß estradiol induce vitellogenin-like proteins in the clam Tapes philippinarum? Environmental toxicology and pharmacology. 26: 38-44.

- Lister AL, Van Der Kraak GJ. (2001). Endocrine disruption: why is it so complicated? Water Quality Research Journal of Canada. 36: 175-190.

- Guttmacher Institute. (2008). Facts on contraceptive use. In Institute, G., Ed; Washington DC.

- Ying GG, Kookana RS, Ru YJ. (2002). Occurrence and fate of hormone steroids in the environment. Environment international. 28: 545-551.

- Carrera EP, García-López A, del Río MDPM, et al. (2007). Effects of 17ß-estradiol and 4-nonylphenol on osmoregulation and hepatic enzymes in gilthead sea bream (Sparus auratus). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C. Toxicology & Pharmacology. 145: 210-217.

- Maria VL, Ahmad I, Santos MA. (2008). Juvenile sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.) DNA strand breaks and lipid peroxidation response following 17 ß-estradiol two mode of exposures. Environment international. 34: 23-29.

- Johnson AC, Belfroid A, Di Corcia A. (2000). Estimating steroid oestrogen inputs into activated sludge treatment works and observations on their removal from the effluent. Science of the Total Environment. 256: 163-173.

- Lintelmann J, Katayama A, Kurihara N, Shore L, Wenzel A. (2003). Endocrine disruptors in the environment (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 75: 631-681.

- Ternes TA. (1998). Occurrence of drugs in German sewage treatment plants and rivers. Water research. 32: 3245-3260.

- Liu ZH, Kanjo Y, Mizutani S. (2009). Removal mechanisms for endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) in wastewater treatment-physical means, biodegradation, and chemical advanced oxidation: a review. Science of the Total Environment. 407: 731-748.

- Ternes TA, Stumpf M, Mueller J, et al. (1999). Behavior and occurrence of estrogens in municipal sewage treatment plants-I. Investigations in Germany, Canada and Brazil. Science of the Total Environment. 225: 81-90.

- Baronti C, Curini R, D'Ascenzo G, et al. (2000). Monitoring natural and synthetic estrogens at activated sludge sewage treatment plants and in a receiving river water. Environmental Science & Technology. 34: 5059-5066.

- Nasu M, Goto M, Kato H, et al. (2001). Study on endocrine disrupting chemicals in wastewater treatment plants. Water Science & Technology. 43: 101-108.

- Singh SP, Azua A, Chaudhary A, et al. (2010). Occurrence and distribution of steroids, hormones and selected pharmaceuticals in South Florida coastal environments. Ecotoxicology. 19: 338-350.

- Oguz AR, Kankaya E. (2013). Determination of selected endocrine disrupting chemicals in Lake Van, Turkey. Bulletin of environmental contamination and toxicology. 91: 283-286.

- Valdés ME, Marino DJ, Wunderlin DA, et al. (2015). Screening Concentration of E1, E2 and EE2 in Sewage Effluents and Surface Waters of the “Pampas” Region and the “Río de la Plata” Estuary (Argentina). Bulletin of environmental contamination and toxicology. 94: 29-33.

- Díaz-Torres E, Gibson R, González-Farías F, et al. (2013). Endocrine Disruptors in the Xochimilco Wetland, Mexico City. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 224: 1-11.

- Seiler JP. (2002). Pharmacodynamic activity of drugs and ecotoxicology?can the two be connected? Toxicology Letters. 131: 105-115.

- Desbrow CEJR, Routledge EJ, Brighty GC, et al. (1998). Identification of estrogenic chemicals in STW effluent. 1. Chemical fractionation and in vitro biological screening. Environmental Science & Technology. 32: 1549-1558.

- Fent K, Weston AA, Caminada D. (2006). Ecotoxicology of human pharmaceuticals. Aquatic toxicology. 76: 122-159.

- Ahmad I, Maria VL, Pacheco M, Santos MA. (2009). Juvenile sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.) enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant responses following 17ß-estradiol exposure. Ecotoxicology. 18: 974-982.

- Thilagam H, Gopalakrishnan S, Qu HD, Bo J, Wang KJ. (2010). 17 ß estradiol induced ROS generation, DNA damage and enzymatic responses in the hepatic tissue of Japanese sea bass. Ecotoxicology. 19: 1258-1267.

- Rose J, Holbech H, Lindholst C, et al. (2002). Vitellogenin induction by 17 ß-estradiol and 17a-ethinylestradiol in male zebrafish (Danio rerio). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology. 131: 531-539.

- Thomas-Jones E, Thorpe K, Harrison N, et al. (2003). Dynamics of estrogen biomarker responses in rainbow trout exposed to 17ß-estradiol and 17a-ethinylestradiol. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 22: 3001-3008.

- Kang IJ, Yokota H, Oshima Y, et al. (2002). Effect of 17ß-estradiol on the reproduction of Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes). Chemosphere. 47: 71-80.

- Jobling S, Casey D, Rodgers-Gray T, et al. (2004). Comparative responses of molluscs and fish to environmental estrogens and an estrogenic effluent. Aquatic Toxicology. 65: 205-220.

- Robinson CD, Brown E, Craft JA, et al. (2007). Bioindicators and reproductive effects of prolonged 17ß-oestradiol exposure in a marine fish, the sand goby (Pomatoschistus minutus). Aquatic toxicology. 81: 397-408.

- Lei B, Kang J, Yu Y, et al. (2013). ß-estradiol 17-valerate affects embryonic development and sexual differentiation in Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes). Aquatic toxicology. 134: 128-134.

- Teles M, Gravato C, Pacheco M, Santos MA. (2004). Juvenile sea bass biotransformation, genotoxic and endocrine responses to ß-naphthoflavone, 4-nonylphenol and 17ß-estradiol individual and combined exposures. Chemosphere. 57: 147-158.

- Costa DM, Neto FF, Costa MDM, et al. (2010). Vitellogenesis and other physiological responses induced by 17-ß-estradiol in males of freshwater fish Rhamdia quelen. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology. 151: 248-257.

- Livingstone DR. (2001). Contaminant-stimulated reactive oxygen species production and oxidative damage in aquatic organisms. Marine pollution bulletin. 42: 656-666.

- Lushchak VI. (2011). Environmentally induced oxidative stress in aquatic animals. Aquatic Toxicology. 101: 13-30.

- Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, et al. (2007). Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 39: 44-84.

- Matés JM. (2000). Effects of antioxidant enzymes in the molecular control of reactive oxygen species toxicology. i 153: 83-104.

- Valko M, Rhodes CJ, Moncol J, et al. (2006). Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chemico-biological interactions. 160: 1-40.

- Al-Sabti K, Metcalfe CD. (1995). Fish micronuclei for assessing genotoxicity in water. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology. 343: 121-135.

- Huang DJ, Zhang YM, Song G. (2007). Contaminants-induced oxidative damage on the carp Cyprinus carpio collected from the upper Yellow River, China. Environmental monitoring and assessment. 128: 483-488.

- Oruç EÖ, Usta D. (2007). Evaluation of oxidative stress responses and neurotoxicity potential of diazinon in different tissues of Cyprinus carpio. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 23: 48-55.

- Scarcia P, Calamante G, la Torre F. (2012). Responses of biomarkers of a standardized (Cyprinus carpio) and a native (Pimelodella laticeps) fish species after in situ exposure in a periurban zone of Luján river (Argentina). Environmental toxicology. 29: 545-557.

- Yamanaka H, Sogabe A, Handoh IC, et al. (2011). The effectiveness of clove oil as an anaesthetic on adult common carp, Cyprinus carpio L. Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances. 10: 210-213.

- Jiang ZY, Hunt JV, Wolff SP. (1992). Ferrous ion oxidation in the presence of xylenol orange for detection of lipid hydroperoxide in low density lipoprotein. Analytical biochemistry. 202: 384-389.

- Büege JA, Aust SD. (1978). Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods in enzymology. 52: 302-310.

- Levine RL, Williams JA, Stadtman ER, Shacter E. (1994). Carbonyl assays for determination of oxidatively modified proteins. Methods in enzymology. 233: 346-57.

- Parvez S, Raisuddin S. (2005). Protein carbonyls: novel biomarkers of exposure to oxidative stress-inducing pesticides in freshwater fish Channa punctata (Bloch). Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 20: 112-117.

- Misra HP, Fridovich I. (1972). The role of superoxide anion in the autoxidation of epinephrine and a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. Journal of Biological chemistry. 247: 3170-3175.

- Radi R, Turrens JF, Chang LY, et al. (1991). Detection of catalase in rat heart mitochondria. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 266: 22028-22034.

- Gunzler W, Flohe-Clairborne A. (1985). Glutathione peroxidase. In R. A. Green-Wald (Ed.), Handbook of methods for oxygen radical research. Boca Raton: CRC Press. 285-290.

- Stephensen E, Svavarsson J, Sturve J. (2000). Biochemical indicators of pollution exposure in shorthorn sculpin (Myoxocephalus scorpius), caught in four harbours on the southwest coast of Iceland. Aquatic Toxicology. 48: 431-442.

- Bradford MM. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical biochemistry. 72: 248-254.

- Swart N, Pool E. (2007). Rapid detection of selected steroid hormones from sewage effluents using an ELISA in the Kuils River water catchment area, South Africa. Journal of immunoassay & immunochemistry. 28: 395-408.

- EMEA. (2006). European Medicines Agency Pre-Authorization. Evaluation of medicines for human use. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), (Doc. Ref. EMEA/CHMP/SWP/ 4447/00) 12.

- Guengerich FP. (1990). Metabolism of 17alpha-ethynylestradiol in humans. Life Sciences. 47: 1981-1988.

- Carballa M, Omil F, Lema JM, et al. (2004). Behavior of pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and hormones in a sewage treatment plant. Water Research. 38: 2918-2926.

- Legler J, Jonas A, Lahr J, et al. (2002). Biological measurement of estrogenic activity in urine and bile conjugates with the in vitro ER-CALUX reporter gene assay. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 21: 473-479.

- Bièche I, Narjoz C, Asselah T, et al. (2007). Reverse transcriptase-PCR quantification of mRNA levels from cytochrome (CYP) 1, CYP2 and CYP3 families in 22 different human tissues. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 17: 731-742.

- Jönsson ME, Orrego R, Woodin BR, et al. (2007). Basal and 3, 3', 4, 4', 5-pentachlorobiphenyl-induced expression of cytochrome P450 1A, 1B and 1C genes in zebrafish. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 221: 29-41.

- Goldstone JV, Jönsson ME, Behrendt L, et al. (2009). Cytochrome P450 1D1: a novel CYP1A-related gene that is not transcriptionally activated by PCB126 or TCDD. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 482: 7-16.

- Cavalieri E, Frenkel K, Liehr JG, et al. (2000). Estrogens as endogenous genotoxic agents?DNA adducts and mutations. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 27: 75-93.

- Valavanidis A, Vlahogianni T, Dassenakis M, Scoullos M. (2006). Molecular biomarkers of oxidative stress in aquatic organisms in relation to toxic environmental pollutants. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety. 64: 178-189.

- Eruslanov E, Kusmartsev S. (2010). Identification of ROS using oxidized DCFDA and flow-cytometry. In Advanced Protocols in Oxidative Stress II. Humana Press. 57-72

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. (1999). Free radicals in biology and medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Salganik RI. (2001). The benefits and hazards of antioxidants: controlling apoptosis and other protective mechanisms in cancer patients and the human population. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 20(sup5), 464S-472S

- Niki E, Yoshida Y, Saito Y, Noguchi N. (2005). Lipid peroxidation: mechanisms, inhibition, and biological effects. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 338: 668-676.

- Wilhelm Filho D, Torres MA, Zaniboni-Filho E, Pedrosa RC. (2005). Effect of different oxygen tensions on weight gain, feed conversion, and antioxidant status in piapara, Leporinus elongatus (Valenciennes, 1847). Aquaculture. 244: 349-357.

- Pesonen M, Celander M, Förlin L, Andersson T. (1987). Comparison of xenobiotic biotransformation enzymes in kidney and liver of rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri). Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 91: 75-84.

- Zhu BT, Bui QD, Weisz J, Liehr JG. (1994). Conversion of estrone to 2-and 4-hydroxyestrone by hamster kidney and liver microsomes: implications for the mechanism of estrogen-induced carcinogenesis. Endocrinology. 135: 1772-1779.

- Shou M, Korzekwa KR, Brooks EN, et al. (1997). Role of human hepatic cytochrome P450 1A2 and 3A4 in the metabolic activation of estrone. Carcinogenesis. 18: 207-214.

- Zhu BT, Conney AH. (1998). Functional role of estrogen metabolism in target cells: review and perspectives. Carcinogenesis. 19: 1-27.

- Tabakovic K, Gleason WB, Ojala WH, Abul-Hajj YJ. (1996). Oxidative transformation of 2-hydroxyestrone. Stability and reactivity of 2, 3-estrone quinone and its relationship to estrogen carcinogenicity. Chemical research in toxicology. 9: 860-865.

- Jifa W, Yu Z, Xiuxian S, You W. (2006). Response of integrated biomarkers of fish (Lateolabrax japonicus) exposed to benzo [a] pyrene and sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety. 65: 230-236.

- Stadtman ER. (2004). Role of oxidant species in aging. Current medicinal chemistry. 11: 1105-1112.

- Nadkarni DV, Sayre LM. (1995). Structural definition of early lysine and histidine adduction chemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal. Chemical research in toxicology. 8: 284-291.

- Monteiro SM, Mancera JM, Fontaínhas-Fernandes A, Sousa M. (2005). Copper induced alterations of biochemical parameters in the gill and plasma of Oreochromis niloticus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology. 141: 375-383.

- Halliwell B. (2006). Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? Journal of neurochemistry. 97: 1634-1658.

- Eaton P. (2006). Protein thiol oxidation in health and disease: techniques for measuring disulfides and related modifications in complex protein mixtures. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 40: 1889-1899.

- Stadtman ER, Levine RL. (2003). Free radical-mediated oxidation of free amino acids and amino acid residues in proteins. Amino acids. 25: 207-218.

- Cabiscol E, Tamarit J, Ros J. (2010). Oxidative stress in bacteria and protein damage by reactive oxygen species. International Microbiology. 3: 3-8.

- Glusczak L, Dos Santos Miron D, Moraes BS, et al. (2007). Acute effects of glyphosate herbicide on metabolic and enzymatic parameters of silver catfish (Rhamdia quelen). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology. 146: 519-524.

- Bebianno MJ, Company R, Serafim A, et al. (2005). Antioxidant systems and lipid peroxidation in Bathymodiolus azoricus from Mid-Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal vent fields. Aquatic toxicology. 75: 354-373.

- Wilhelm Filho D. (1996). Fish antioxidant defenses-a comparative approach. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research. 29: 1735-1742.

- Van der Oost R, Beyer J, Vermeulen NP. (2003). Fish bioaccumulation and biomarkers in environmental risk assessment: a review. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology. 13: 57-149.

- Livingstone DR. (2003). Oxidative stress in aquatic organisms in relation to pollution and aquaculture. Revue de Medecine Veterinaire. 154: 427-430.

- Azzi A, Davies KJ, Kelly F. (2004). Free radical biology? terminology and critical thinking. FEBS Letters. 558: 3-6.

- Solé M, Porte C, Barcelo D. (2000). Vitellogenin induction and other biochemical responses in carp, Cyprinus carpio, after experimental injection with 17a-ethynylestradiol. Archives of environmental contamination and toxicology. 38: 494-500.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences