A Biological Theory of Emotions

Thomas Scheff

Thomas Scheff*

Professor Emeritus of Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara, USA

Received date: February 15, 2016; Accepted date: February 26, 2016; Published date: March 06, 2016

Citation: Scheff T, A Biological Theory of Emotions. Electronic J Biol, 12:2

Abstract

This note suggests a way of defining emotion based on the work of John Dewey and Nina Bull. Oddly, emotions go undefined in most current emotion research, creating chaos. Dewey proposed that emotions are bodily preparations for internal actions that have been delayed, but he didn't provide a single example. Bull provided one: grief is bodily preparation to cry, but the crying has been delayed. No delay, no pain. This step enables the reader to understand her theory, even though, like Dewey, much of the discussion is not clear or neglects crucial matters. She leaves out pride, shame and "efatigue"(excessive fatigue) entirely, which this article introduces. She also doesn't consider why emotions can be experienced as "good" or "bad". The distancing theory of emotions developed in the theatre suggests that backlogged emotion can either be merely relived (a bad grief, anger, shame, efatigue or fear) or, at what is called "aesthetic distance," as a relief from pain. Examples are given of the author's experience of a good anger, fear, shame, and efatigue. This approach suggests that the idea of negative emotions is an illusion: emotions may be like breathing, only painful when obstructed. Even if true, it will difficult for it to be considered, since the belief that some emotions are inherently negative seems to be a powerfully defended trope in modern societies.

Keywords

Grief; Anger; Fear; Shame; Distancing.

Introduction

The serious study of emotions by a large number of people is relatively new. It began considerably less than a hundred years ago. Relative to the study of behavior, thought, perception, social structure and other well-established fields, sustained interest in emotions is still in its infancy. Perhaps it is mainly for this reason that understanding the realm of emotions is still beset by an elemental difficulty: the meanings of words that refer to emotion are so confused that we hardly know what we are talking about. Virginia Woolf wrote: “The streets of London have their map; but our passions are uncharted” [1].

Experts disagree on almost everything about emotions. Several studies have pointed out the lack of agreement. Ortony et al. [2] reported on twelve investigators, some leading experts in the field. Even the number, much less the specific emotions, is in contention; the fewest proposed is two, the most, and eleven. There is not a single emotion word that shows up on all 12 lists. Plutchick [3] also showed wide ranging disagreement of the 16 leading theorists (p. 73).

This disagreement involves emotion words in only one language, English. The comparison of different languages opens up a second level of chaos. Anthropological and linguistic studies suggest that just as the experts disagree on the number and names of the basic emotions, so do languages. Cultural differences in emotion words will be mentioned here, but it is too large an issue to be discussed at length.

The supply of emotion words in the West, particularly in English, is relatively small. Although English has by far the largest total number of words (some 800,000 and still expanding), its emotion lexicon is smaller than other languages, even tiny languages like Maori. In addition to having a larger emotion lexicon than English, its emotion words are relatively unambiguous and detailed compared to English [4]. Mandarin Chinese provides another example of a classical language which deals with emotions much more clearly than the languages of modern societies, particularly English. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to UCSB, Santa Barbara, California, 93106.

1.1 Emotion terms

In my days as a physics graduate student, I learned that scientific terms require both conceptual and operational definitions. General concepts require a clear, unitary and abstract definition. Operational definitions are specifically about how the concept is to be measured. These rules allow for no ambiguity whatsoever. But emotion terms, especially in English, are wildly ambiguous.

Grief: In this case, ambiguity might seem to amount only to the choice of words. Most authors use the term grief to refer to the emotion of loss. But there is a large literature on attachment in which the authors use the term distress instead. Distress is broader than grief and seems to imply consciousness and pain more than grief.

For reasons that he didn’t make clear, Silvan Tomkins [5], a pioneer in the study of emotions, seems to have started the use of the word distress. In the first three volumes of his influential study (1962; 1963; 1965; 1992) the word is used frequently, with grief occurring only once. However, in V. 4, there is a sharp change; distress disappears, its place taken by grief. In the first three volumes it is fairly clear what he means, because he connects distress to loss and crying. In IV, he makes this connection using only the word grief. What happened? As far as I know, there has been no published response to this dramatic change in nomenclature.

The original studies of facial expression of emotion followed Tompkins' first usage: neither Ekman and Friesen [6] nor Izard [7] refers to grief. However, later works, such as Harre’ and Parrott [7], refer only to grief, never to distress. Plutchick [3] also refers only to grief. Others use the word sadness, rather than distress or grief. Still another direction is followed by Volkan and Zintl [8]. They elide around both grief and distress by referring only to failure to mourn. It would seem that anarchy rules in the naming of the emotion associated with loss and crying.

Fear/anxiety: Before Freud, fear meant the emotional signal of physical danger to life or limb, and anxiety was just a more diffuse kind of fear. But after Freud, the meaning of these words began to expand. Anxiety became broader, enough to include many kinds of diffuse emotion, but not as broad as “emotional arousal”. Current vernacular usage is so enlarged that fear can be used to mask other emotions, especially shame and humiliation. “I fear rejection” has nothing to do with danger of bodily harm, nor does “social fear” or “social anxiety”. These terms refer rather to the anticipation of shame or humiliation. As will be discussed further below, modern societies go to great lengths to avoid mentioning what might be called "the s-word". Indeed, it seems to be more avoided than even the f-word.

Anger: the confusion over the meaning of this word seems different than any of the above. It involves confounding the feeling of anger with acting out anger, confusing emotion with behavior. We don’t confuse the feeling of fear with running away, the feeling of shame with hiding one’s face, or the feeling of grief with crying. But anger is thought to be destructive, even though it is only a feeling.

The feeling of anger is an internal event, like any other emotion. It is one of the many pain signals that alert us to the state of the world inside and around us. In itself, if not acted out, it is instructive, not destructive. The condemnation of emotions as negative in Western societies is another aspect of chaos. Normal emotions, at least, are not negative, since they are brief, instructive and vitally necessary for survival. Like breathing, emotions are troublesome only when they are obstructed. Yet almost everybody is completely sure that many emotions are by their nature completely negative. When anger is expressed verbally, rather than acted out as yelling or aggression, it can be constructive. It explains to self and other how one is frustrated, and why. Both self and other need to know this information. The confounding of anger expression with acting out can be a seen as a way of justifying aggression, as in spousal abuse and road rage. “I couldn’t help myself”.

Shame: Substitute terms for anger usually don’t hide the emotion; they just soften the reference to it: "pissed off". With shame, however, most of the many substitute words and phrases hide the reference entirely. Current usage of shame in English aims toward an extremely narrow meaning: a crisis feeling of intense disgrace. In this usage, a clear distinction is made between embarrassment and shame. Embarrassment can happen to anyone, but shame is conceived as horrible. Embarrassment is speakable, shame is unspeakable. This usage avoids everyday shame such as embarrassment and modesty, and in this way sweeps most shame episodes under the rug.

Other languages, even those of modern societies, treat embarrassment as a milder version of shame. In Spanish, for example, the same word (verguenza) means both. Most languages also have an everyday shame that is considered to belong to the shame/ embarrassment family. French pudeur, which is translated as modesty, or better yet, a sense of shame, is differentiated from honte, disgrace shame. If you ask an English speaker is shame distinct from embarrassment, they will usually answer with an impassioned yes. But a French speaker might ask “Which kind of shame?”

Suppose that just as fear signals danger of bodily harm, and grief signals loss, shame signals disconnection. This signal appears to be mammalian: all mammals, not just humans, are vitally concerned with being accepted by their individuals and their group. In modern societies, because of individualism, deeply connecting with others is somewhat infrequent, we can hide that fact. Instead of saying that we were embarrassed, we say “It was an awkward moment for me”. It was the moment that was awkward (projection), not me that was embarrassed (denial).

In English especially, there is a vast supply of code words that can be used as alternatives to the s-word [9]. She lists more than a hundred vernacular words that may stand for shame, under six headings:

• Alienated: rejected, dumped, deserted, etc.

• Confused: blank, empty, hollow, etc.

• Ridiculous: foolish, silly, funny, etc.

• Inadequate: powerless, weak, insecure, etc.

• Uncomfortable: restless, tense, anxious, etc.

• Hurt: offended, upset, wounded, etc.

The broadening use of fear and anxiety is another way of disguising shame. To say that one fears rejection or to use a term like social anxiety is to mask the common occurrence of shame and embarrassment. We can also disguise the pain of rejection by acting out anger or withdrawal. Studies of stigma, even though this word means shame, seldom take note of the underlying emotion, concentrating instead on thoughts and behavior.

Apologies suggest another instance of the masking of shame with another emotion. The ritual formula for an apology in English is to say that you are sorry. But the word sorry (grief) serves to mask the more crucial emotion of shame. “I’m ashamed of what I did” is a much more potent apology than the conventional “I’m sorry”.

The masking of shame with substitute words occurs not only in the public by also in research. Although most dictionaries define stigma in terms of shame, the vast scholarly literature hardly mentions it, much less defining stigma as a type of shame. Many other fields of study also mask their relation to shame, such as rejection, exclusion, disrespect, stigma, honor cultures, revenge, etc [10]. Modern societies seem to teach their members to be ashamed of shame in some fundamental and lasting way.

The word pride in English is also problematic. Unless one precedes the word with “justified, authentic or genuine”, there is an inflection of arrogance, “the pride that goeth before the fall”. Pride is also listed as one of the deadly sins [11,12]. This type would better be called egotism, or false pride, since it implies hiding shame behind boldness or egotism. False pride is only one more way of hiding shame.

From my experience with these problems, it seems to me that the emotion language and ideas in modern societies are not just tropes, but a special type of trope. An ordinary trope is a widespread belief held so firmly that it goes without saying [13]. The vast structure of beliefs in a society is made up of interlocking tropes, but some of them are strongly defended against change of any kind. Kepler's discovery that the planets revolve the sun rather than the earth probably wasn't a huge shock to the public; their daily life didn't depend on it. But the idea that some emotions are positive and others negative seems to be a crucial trope, one that will be defended as if peoples' lives depended on it, and will continue to face virtually immovable resistance to change.

1.2 What is an emotion?

Even more fundamental than the disagreements over the meaning of specific emotion terms, there is no agreement over the term emotion itself. Most emotion researchers use it as a vernacular word, just as they do with the terms for specific emotions. They apparently think, like the public, that the meaning of emotion is clear, just as they act as if the meanings of specific emotion terms are clear. But as proposed earlier, these meanings are massively confused and confusing. What can be done?

Long ago, John Dewey [14] took a first step toward the problem of defining an emotion. Apparently influenced by discussions of the physical nature of emotion, such as those by James [15] and Darwin [16], he proposed that emotion involves bodily preparations for internal actions that have been delayed. But there were two problems with his offering. First, in calling his approach "the attitude theory of emotion", he used the word "attitude" in a way it is seldom used today. The usual meaning involves a cognitive disposition. But Dewey used it in its second meaning, not a cognitive, but any kind of disposition.

The second problem is especially crucial: Dewey didn't bother to show how it applies to a specific emotion. As if often the case in dealing with emotions, his discussion was general and abstract, lacking specific examples. I think this is the main reason that most emotion experts have not used them. Schore [17,18], for example, also discusses the bodily bases of emotion, but doesn't refer to Dewey.

Nina Bull's book [19], on the other hand, uses Dewey's idea, but unlike Dewey, she does offer a useful application to a specific emotion, even though it is easily missed by the casual reader. On the face of it, her book reports on a systematic study of verbal reports of her subjects on the anger and fear she induced in them. However, like most systematic studies of emotion, she doesn't offer sufficient definitions of anger and fear. She also interprets the way her subjects reported their responses to anger and to fear inductions in her lab as clear and obvious.

But to me neither the vernacular meaning of these two words is clear, nor the reports of her subjects on their anger and fear responses. For this reason, the book as a whole was disappointing. However, in the introduction, Bull does offer descriptions of three emotions. Oddly, since her study deals entirely with anger and fear, she gives the fullest definition of a different emotion, one that doesn't occur again in the rest of the book.

In the introduction, she begins to illustrate her theory in this sentence:

...the sorry feeling is mediated by the attitude of readiness...to cry, and not by actually crying (p. 6).

She seems to be saying that the emotion of grief arises from readiness to cry.

She goes on: The fact is that we feel less sorry when we start to cry in good earnest; and crying that is violent enough eliminates the sorry feeling altogether (p.6).

These two sentences about a specific emotion (grief) make Dewey's abstract definition understandable. I think this is an important book for that reason, although it takes a close reading to find it. Grief is bodily preparation for crying that had been delayed. She means that if one cries immediately upon loss, little or no pain would be experienced. This idea clarifies what seems to be confusion in the tendency that people have to think that emotions have a cognitive component. In Bull's approach, all emotions are somatic only; they are mammalian preparations for internal bodily actions. Feeling emotion occurs only when the resolution of these preparations, such as preparing to sob and tears, is delayed.

This definition seems to be a good start, because it offers two crucially important ingredients of grief: the external stimulus (loss) and the physical nature of the bodily preparation that is delayed: preparing to cry (sobbing and tears). This formulation is a step ahead of Dewey's for this reason. Surprisingly, my mentor during graduate school at Berkeley, Tom Shibutani, had not only read Bull's book, but had even understood that the sentences above were what was important in the book [20]. It appears that he was more than 50 years ahead of me in this respect. I suspect that the reason he read Bull's book was that he was a serious student of John Dewey's work. The crucial sentences on crying have also been noticed more recently by Daniel Lewis [19] in his article on Bull's life.

Bull goes on to try to define anger and fear: "we feel anger as a result of readiness to strike" and "feel afraid as a result of readiness to run away" Unfortunately, she doesn't offer the physical state that follows from the readiness, as she offered crying for grief. For anger and fear, she proposes only the stimuli. However, she does take a step in that direction: she doesn't name the physical preparation, but her discussion of preparing for fight, flight and freezing up (imitating death, as is clear with animals) might be seen as a step in that direction.

Preparing for flight means generating adrenalin for running away, also the case with anger, preparing to fight. But what kind of preparation does freezing up imply? One answer would be that it is intense muscular contractions in the whole body. If that is the case, then just as the metabolizing of the adrenalin would be one of the components of completion, then shaking or trembling would be the other. A more complete definition of the bodily response to immediate danger may be deduced from her discussion: body heat that metabolizes the stored up adrenalin almost instantly, and shaking that relaxes all of the muscular contractions that occur in freezing up.

I have not found this interpretation of the completion of the mammalian fight and flight/freeze pattern in the biological literature. For example, Hagenaars et al. [21] provide a lengthy discussion of the literature on the freeze pattern in humans and other mammals, but do not offer a discussion of bodily completion of the freeze. However, Levine's [22] book on treating trauma is based on a fear model like the one proposed here. There are also several articles that refer to Levine's book, such as Duros and Crowley [23]. Apparently Levine's book has produced a worldwide approach to the treatment of trauma called Somatic Experiencing.

Although there are several emotion matters in the Levine text that might require further discussion, the one that stands out is the strong emphasis on the freeze-trembling response to fear, but with the flightbody heat response barely mentioned. If, as Nina Bull's book proposes, fear is a biologically built-in response, then both trembling and sweating would always equally necessary, no matter the nature of the stimulus that produced the fear.

1.3 The distancing of emotions

Another issue with Bull's proposals is that they don't mention that grief, anger and fear can occur in at least two different patterns. One can have a good cry, one that ends the painful grief, or a bad one, which seems to have no effect at all or even, increases the pain. Since these differences have hardly been mentioned, much less systematically studied, I have had to rely on my own personal experiences of emotion.

My moments of anger and of fear have been strongly divided into the good and the bad kind. Most of my angry moments have involved venting, raising my voice, and often rudely condemning the other person. I call these moments bad anger, because they leave me in a state of agitation, often for hours afterwards, to say nothing of the effects on the recipient of the anger. Most of my fear responses have been similar; the resulting agitation lasts a long time after the incident is over.

However, I have also had incidents of good anger, fear and shame. The following is an example of good anger. Many years ago on a short airplane flight, I happened to be seated by chance on the plane next to Karl Pribram, at that time a psychologist on my campus (UCSB) and very much my senior. Nevertheless, still full of my own recent experience, I couldn't stop myself from telling him about an emotional completion I had the night before. He interrupted me after a few sentences, however, coolly analyzing what I had said. I became angry and interrupted him in turn. I blurted out: “Professor Pribram, you are trying to reduce my experience to yours, and I won’t have it”. Although I spoke the words quickly, they were not loud or demeaning.

Three things happened: Dr. Pribram began apologizing at length, I felt calm, and the plane seemed to get hot. I was very surprised at my calmness, since anger usually made me hyper for hours. Looking at other people on the plane, I realized it wasn’t the plane that was hot, it was me. As proposed by the discussion of Nina Bull's theory above, a rise in body temperature could have instantly metabolized the adrenalin rush that comes with anger.

This idea was new at the time, since I had been taught that venting led to the resolution of unresolved anger, “getting it off your chest”. I was skeptical about this idea, since I suspected that venting didn’t help, and certainly was bad news to the recipient(s). Although I didn't know it at the time, Berkowitz [24] and many others had conducted experiments showing that venting anger doesn't help. It now seemed to me that the best way to deal with anger would be to explain the reason for it to whoever was responsible for it, as I did with Pribram. In this way, it is possible to maintain aesthetic distance, rather than bestowing the present anger and at least some of the backlog on the unhappy recipient(s).

1.4 A death threat

The example of my unusual fear response involved an anonymous phone call. With the other campus Vietnam protest leaders, I was planning a large on-campus event. This plan was causing friction, because the Chancellor had specifically forbidden it, as well as all other protests on campus. I got several phone calls from colleagues in other departments objecting. Some of the callers were vehement; one challenged me to a fist fight.

The morning of the protest, I was awakened in my apartment by an anonymous phone call. He said I was the one stirring up the students, and that he planned to kill me and my family. I was upset by the call, particularly the part about my family. I was so upset that I thought I would be unable to speak as planned at the protest.

An earlier self-help therapy class had taught me to repeat a mantra over and over concerning whatever emotion might be hidden behind upsets. So I begin repeating “I am afraid”. It occurred to me that I hadn’t said or even thought that sentence since childhood, like most other men. After a sizeable number of repetitions, I begin to shake with such force that I lowered myself to the rug, so as not to fall. I was also sweating to the point that I soaked my clothes. I had no thoughts.

After some 15 or 20 minutes, the shaking/sweating fit stopped. I got up, took a shower and got dressed in clean clothes. I was just in time to get to the protest, where I gave a brief extempore talk that moved the audience. The fear resolution had cleared my head to the point where I knew I would need no preparation.

Finally, here is an example of my experience of good shame. The night of my first class in a self-help group therapy class, I was telling my then girlfriend about it. As if to illustrate what the class was like, I proceeded, without willing it, to laugh about myself for at least twenty minutes. The laughter was involuntary, but it was also deeply soothing and relaxing. It seemed different than my usual laugh, in that I had the feeling that my whole body was involved. When it ended, I felt like a new person

Why did I have these very different kinds of emotional experience that resolved, rather than increased the pain? The following is an explanation that has been offered in drama theory for some two thousand years, beginning with Aristotle.

1.5 The distancing of emotion

As indicated above, psychologists have long been conducting experiments that show that venting anger doesn’t work [24]. This is an advance in knowledge, an important finding because the public thinks that venting is a good idea, that it gets anger “off your chest.” However, the venting researchers have made what might be an error in evaluating the meaning of what they found: they think that they have refuted the idea of catharsis. They seem to have completely ignored the large literature in the humanities that has developed a complex model. According to this model, venting is not a form of catharsis. Arousing anger in a theatre audience is meant to let them feel emotions safely, not cause a riot. The poet Wordsworth's (1800, p. 12) phrase "emotions recollected in tranquility" points toward the central idea of catharsis.

The drama theory of catharsis proposes that it occurs only at "aesthetic" distance, between overdistanced (no emotional reaction) and underdistanced (a mere reliving, rather than a resolution of backlogs of emotional experiences). In this view, venting anger is underdistanced, and therefore not a form of catharsis. A central aspect of catharsis that needs to be studied is the way in which persons at aesthetic distance both feel hitherto hidden emotions and seemingly at the same time, watch themselves feeling them. Apparently it provides a safe zone; if it appears that it might be too painful, the observing self can stop the process; one can leave the theatre, so to speak.

Studies could be somewhat difficult, since pendulation may be extremely rapid. The word pendulation [22] suggests a fairly slow movement (like a clock pendulum), so another term, like role-taking, may be needed to understand the way that we learn and use language. In modern societies, we not only learn a huge complex language, but also learn to be extremely quick in using it. To follow the need to be judged competent in conversation, or at least not ridiculed, consider the complexity and ambiguity of ordinary human discourse.

Human languages in actual usage are almost always fragmented, incomplete, and context dependent, with most commonly used words having more than one meaning. For these reasons, even simple discourse would be impossible to understand directly, taken literally. We understand the speech of others to the extent that we can take on, however briefly, their point of view. This necessity gives rise to complex multiprocessing.

Scholars have suggested that the self is made up of movement between own self and the point of view of other(s). They begin by pointing to the learning of language: what seems to make the various human languages possible, as opposed to the small instinctive vocabularies of other mammals, is what Mead [25] called role-taking. Humans can imagine the point of view of another person or persons, which helps explain much of the humanness of the human mammal. The imagination is not always accurate, but judging from the speed with which modern societies function, it is accurate enough, enough of the time, to keep the wheels spinning. Even when inaccurate, role-taking fulfills the vital function of taking persons outside of themselves.

Most role-taking by adults appears to occur at lightning speed, so fast that it disappears from consciousness at an early age. In modern societies, particularly, which strongly encourage individualism; there are many incentives for forgetting that one is role-taking. Each of us learns to consider ourselves a stand-alone individual, independent of what others think. “We live in the minds of others without knowing it” [26].

Children learn role-taking so early and so well that they forget they are doing it. The more adept they become, the quicker the movement back in forth, learning through practice to reduce silences in conversation to an unbelievably short time. Studies of recorded conversations of adults such as the one by Wilson and Zimmerman [27] help us understand how forgetting the whole inner process is possible.

Their study analyzed adult dialogues nine minutes long in seven conversations (14 different people). In the segments recorded, the average length of silences varied from 0.04 to 0.09 seconds. How can one possibly respond to the other’s person comment in less than a tenth of a second? Allowing a whole minute silence, rather than a tenth of a second, would make the pace of response SIX HUNDRED times slower.

Apparently one needs to begin forming a response well before the other person has stopped speaking, perhaps even during the first few seconds. That is, humans are capable of multiprocessing, in this case, in a least four different channels: listening to the other’s comment, imagining its meaning from speaker’s point of view, from own point of view, and forming a response to it. These four activities must occur virtually simultaneously. There may be even further channels, such as imagining the other person’s response to our forthcoming comment. These reactions could give rise to very rapid back and forth between two or more channels: a vast interior drama could occur in each person unknowingly in a dialogue, before each response.

For that reason, and because most people become as proficient as children that they quickly forget they are doing it. Studies are needed of second by second role-playing inside the self. Literature provides many extraordinary examples, such as in some of the novels of Virginia Woolf, but I haven't found a study that examined such inner activities directly and systematically.

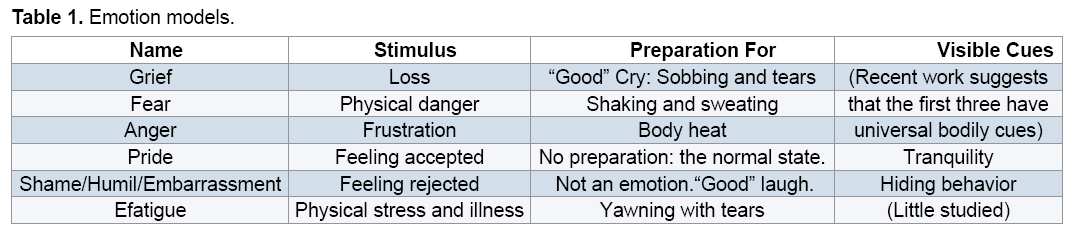

Finally, there are three other responses Nina Bull's book doesn't mention that might be at least as important as grief, anger and fear: pride, shame and what I am going to call excessive fatigue (efatigue). That is, fatigue far more than is produced by exertion. It is understandable that she doesn't deal with love, since it is more complex than just being an emotion ([28], Chapter 6: Genuine Love and Connectedness). But pride, shame and yawning seem to be elemental mammalian responses like grief, fear and anger. In my view, pride is basically a response to being accepted as a member of the group, and shame, the opposite, a signal of threat to the social bond. All mammals need acceptance in order to survive, especial in the early years of their life: humans are no exception. But modern societies, because of their and painful illness. Accompanying the illness was an almost immobilizing fatigue, even though I had almost zero exertion, lying in bed all day and night. I discovered, to my surprise, that I could decrease both pain and fatigue by inducing yawning fits accompanied by massive tearing. These fits didn't end my illness, but they made it bearable (Table 1).

This table proposes that fear is a response to physical intense investment in individualism, tend to hide this need. The mixing up of genuine pride with egotism is one symptom of this problem; the hiding and ignoring of shame, another.

If pride, shame and efatigue are emotions, the next question that Nina Bull's method brings up is: what is the body preparing for that is delayed? My answer for genuine pride (not egotism) is that it is a mistake to classify it as an emotion; it is the natural state of human beings. Calling pride an emotion is one more instance of the massive confusion over emotions in modern societies.

The answer for shame is a new thought for me, brought on by using Nina Bull's method. I now think that shame is a signal of serious danger, like fear. But the danger is not immediate, as in the case of fear, but more long runs. And the danger is not immediate bodily harm or death, but loss of support of other(s) in the long term, and because of that, perhaps, of some of the respect for one's self. So shame is a preparation for dealing with a very specific and very serious kind of loss. The bodily action then, is for a response that signals that the matter didn't turn out to be serious, after all: laughter. Shame is bodily preparation to have a good laugh that has been delayed. Once again, this definition goes against a trope that is deeply held in modern societies, that shame can be resolved by laughter.

A final step is my recommendation to add a new emotion to the list, one that is related to yawning. Fatigue and illness can produce bodily preparation to yawn and tear. Most people assume that yawning is caused by boredom or sleepiness, but systematic studies have failed to support these ideas [29]. I had an intense introduction to massive yawning many years ago when I was suffering from a lengthy danger, and that it involves bodily preparation to shake and sweat. Anger is a response to frustration, and that it involves bodily preparation for heating up the whole body. Authentic pride (as distinguished from the egotistical kind) seems to be the natural state of humans, so it needs no preparation. Shame is a response to real and/or imagined rejection, and it involves bodily preparation to have a good laugh. Finally, a little known response that I have included as an emotion called fatigue: stress and illness can produce bodily preparation to yawn and tear.

This table allows us to return to Nina Bull's point of view. How was she able providing a new definition of grief, but not anger and fear? Perhaps, like many other women, she had many experiences of a "good" grief: crying at aesthetic distance. But no experiences, at least that she recognized, of a good fear or a good anger: fear leading to sweating and shaking, or anger leading to body heat and immediate metabolizing of adrenalin.

2. Summary

This note has clarified the meaning of earlier attempts to define the term emotion by John Dewey and Nina Bull. Bull provides what seems to be a more helpful definition that expands Dewey's: bodily preparation to respond to a stimulus that has been delayed. At least in the case of grief, she provides two basic aspects of emotion: the nature of the stimulus, and the nature of physical preparation that has been delayed. The stimulus in grief is loss, and the body prepares to cry. However, a further step is necessary to understand why emotions often seem negative, the idea of distancing of emotion, of "emotions recollected in tranquility" and 3 other emotions are added that Bull didn't mention [30-36]. These six definitions could be a first step in moving toward better understanding the emotion world.

References

- Virginia W. (1922). Jacob’s Room. Hogarth,London.

- Ortony A, Gerald C, Allan C. (1988). The Cognitive Structure of Emotions. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Plutchick R. (2003). Emotions and Life. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

- Metge J. (1986). In and Out of Touch. Wellington, NZ: Victoria University Press.

- Tomkins S. (1962). Affect Imagery Consciousness. Vol I: The Positive Effects. New York: Springer.

- Ekman P, Friesen W. (1978). Facial Action Coding System. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Harre R, Parrott G. (1996). The emotions: social, cultural and biological dimensions. London: SageIzard, Carroll. 1977. Human Emotions. New York: Plenum

- Volkan K, Vamik D, Zintl E. (1993). Life after Loss: Lessons of Grief. Macmillan Publishing Company,New York.

- Retzinger S. (1995). Identifying Shame and Anger in Discourse. American Behavioral Science.38: 104-113.

- Scheff T, Mateo S. (2013). The S-Word is Taboo: Shame Is Invisible in Modern Societies. Unpublished ms. 2013, Department of Sociology, UCSB, Santa Barbara, California.

- Scheff T. (1994). Bloody Revenge: Emotion, Nationalism and War. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press (Reissued by iUniverse 2000).

- Tracy J, Joey C, Richard R, Kali T.( 2009). Authentic and Hubristic Pride: The Affective Core of Self-esteem and Narcissism. Self and Identity. 8: 196-213.

- Gibbs SC. (2015). Tropes and the generality of laws. The Problem of Universals in Contemporary Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dewey J. (1894). The Theory of Emotion. Psychological Review. 1: 553-568.

- James W. (1884). What is an Emotion? Mind, 9, 34. 188-205. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- DarwinC. (1890).The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

- Schore A. (1994). Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Schore AN. (2003). Affect Regulation and the Repair of the Self. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.15: 99–100.

- Lewis DJ. (2012). Nina Bull: The Work, Life and Legacy of a Somatic Pioneer. International Body Psychotherapy Journal. 11: 45-58.

- Shibutani T. (1961). Society and Personality: An Interactionist Approach to Social Psychology. Englewood Cliffs, N. J. Prentice-Hall.

- Hagenaars M, Oitzl M, Roelofs K. (2014). Updating freeze: Aligning animal and human research. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews.47:165-76.

- Levine PA. (1997). Waking the Tiger. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

- Duros P, Crowley D. (2014). The Body Comes to Therapy Too. Clinical Social Work Journal.47: 237-246.

- Berkowitz L. (2012). Aggressive Behavior. Wiley Online Library.

- Mead GH. (1934). Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Cooley C. (1922). Human Nature and the Social Order. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons

- Wilson TP, Don HZ.(1986). The Structure of Silence between Turns in Two-party Conversation. Discourse Processes.9: 375-390.

- Scheff T.(2011). What’s Love Got to Do with It? Emotions in Pop Songs. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers

- Walusinski O. (2010). The Mystery of Yawning in Physiology and Disease. Karger,Basel.

- Wordsworth W. (1800). Lyrical Ballads. Long and Rees,London.

- Scheff T.(2014). The Ubiquity of Hidden Shame in Modernity. Cultural Sociology.4: 33-45.

- Allan NS. (2012). The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Elias N. (1939). Über den Prozess der Zivilisation. Reprinted in1994 as The Civilizing Process. London: Blackwell.

- Gottschalk L, Winget C,Gleser G. (1969). Manual of Instruction for Using the Gottschalk-Gleser Content Analysis Scales. Berkeley: UC Press.

- Gottschalk LA, Bechtel R. (1995). Computerized measurement of the content analysis of natural language. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine.47: 123-130.

- Bull N. (1951). The Attitude Theory of Emotion. New York: Nervous and Mental Disease Monographs.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences